These three principles are inter-related and mutually reinforcing:

- Consent of the parties

- Impartiality

- Non-use of force except in self-defence and defence of the mandate

1. Consent of the parties

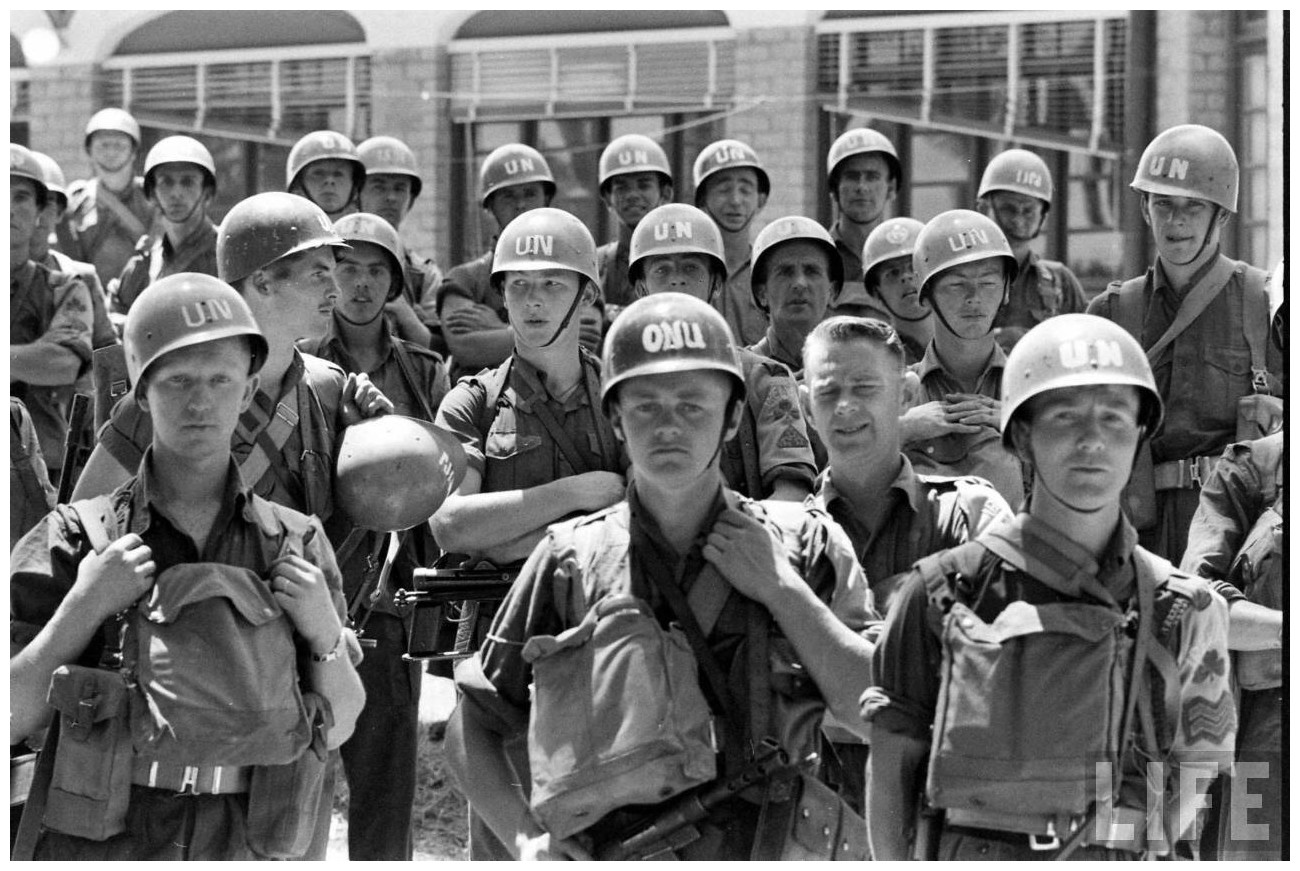

UN peacekeeping operations are deployed with the consent of the main parties to the conflict. This requires a commitment by the parties to a political process. Their acceptance of a peacekeeping operation provides the UN with the necessary freedom of action, both political and physical, to carry out its mandated tasks.

In the absence of such consent, a peacekeeping operation risks becoming a party to the conflict; and being drawn towards enforcement action, and away from its fundamental role of keeping the peace.

The fact that the main parties have given their consent to the deployment of a United Nations peacekeeping operation does not necessarily imply or guarantee that there will also be consent at the local level, particularly if the main parties are internally divided or have weak command and control systems. Universality of consent becomes even less probable in volatile settings, characterised by the presence of armed groups not under the control of any of the parties, or by the presence of other spoilers.

2. Impartiality

Impartiality is crucial to maintaining the consent and cooperation of the main parties, but should not be confused with neutrality or inactivity. United Nations peacekeepers should be impartial in their dealings with the parties to the conflict, but not neutral in the execution of their mandate.

Just as a good referee is impartial, but will penalise infractions, so a peacekeeping operation should not condone actions by the parties that violate the undertakings of the peace process or the international norms and principles that a United Nations peacekeeping operation upholds.

Notwithstanding the need to establish and maintain good relations with the parties, a peacekeeping operation must scrupulously avoid activities that might compromise its image of impartiality. A mission should not shy away from a rigorous application of the principle of impartiality for fear of misinterpretation or retaliation.

Failure to do so may undermine the peacekeeping operation’s credibility and legitimacy, and may lead to a withdrawal of consent for its presence by one or more of the parties.

3. Non-use of force except in self-defence and defence of the mandate

UN peacekeeping operations are not an enforcement tool. However, they may use force at the tactical level, with the authorisation of the Security Council, if acting in self-defence and defence of the mandate.

In certain volatile situations, the Security Council has given UN peacekeeping operations “robust” mandates authorising them to “use all necessary means” to deter forceful attempts to disrupt the political process, protect civilians under imminent threat of physical attack, and/or assist the national authorities in maintaining law and order.

Although on the ground they may sometimes appear similar, robust peacekeeping should not be confused with peace enforcement, as envisaged under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter.

- Robust peacekeeping involves the use of force at the tactical level with the authorization of the Security Council and consent of the host nation and/or the main parties to the conflict.

- By contrast, peace enforcement does not require the consent of the main parties and may involve the use of military force at the strategic or international level, which is normally prohibited for Member States under Article 2(4) of the Charter, unless authorised by the Security Council.

A UN peacekeeping operation should only use force as a measure of last resort. It should always be calibrated in a precise, proportional and appropriate manner, within the principle of the minimum force necessary to achieve the desired effect, while sustaining consent for the mission and its mandate. The use of force by a UN peacekeeping operation always has political implications and can often give rise to unforeseen circumstances.

Judgement’s concerning its use need to be made at the appropriate level within a mission, based on a combination of factors including mission capability; public perceptions; humanitarian impact; force protection; safety and security of personnel; and, most importantly, the effect that such action will have on national and local consent for the mission.